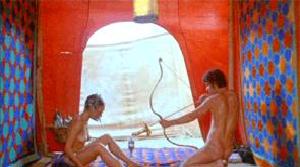

Immoral Tales (Walerian Borowczyk, 1974)

French Title: Contes immoraux

Walerian Borowczyk's Immoral Tales is a collection of four episodes whose common theme seems to be first, an abundance of naked female bodies, and second, naked female bodies participating in what can be conceived as immoral acts. These four episodes belong to four different time lines, different settings, with different degrees of immorality. Despite its judgmental title, Immoral Tales is filmed in unembarrassed objectivity and seems to be more immersed in the portrayal of moving flesh than actual commentary, which isn't all that bad since Borowczyk's camera knows how to light these light-skinned nymphs to the most sensuous and most titillating degree that despite the film's shallow-headed nature, I can't really complain.

The first episode concerns a man who goes to a bicycle trip with his younger cousin. They stop by the beach wherein the man decides to consummate his fantasy with the girl. While teaching the girl how tides work, the girl performs oral sex on the guy. The episode finishes with the girl insisting that there's more time for fun, but is rejected by the guy who says that what they did was not fun, but education. Borowczyk loves to fill his screen with flesh and purposely closes up on the female flesh in frenzied fashion. He intercuts the lovemaking scene with images of the sea, of a duck trying to fight a humongous wave, of seabirds flying by. It's obviously softcore pornography dressed up in art film sensibilities and this is actually the tamest of the bunch. It gets better.

The first episode is followed by the tale of a young girl who gets vocal messages from what she thinks is the Holy Spirit. She is punished by her guardian for disappearing after church service and is trapped inside a room for three days. She doesn't waste the time alone, and starts to look around for things to do, discovering "Therese the Philosopher" by de Sade, while being commanded by the voice that talks to her to let go. In a bizarre mix of de Sade and ignorant religiosity, the girl finds erotic uses for the vegetable left to her.

The third episode is about Countess Bathory (Paloma Picasso) who goes around Hungary's cantons and hamlets to steal away girls and bring them to her palace. Along with her servant, she watches these girls bathe, play, and fight until the time she poisons them all and lets them kill each other over the pearl-adorned dress she has promised to them. Bathory's madness culminates with her bathing in these ladies' blood, and caps the night with ritualistic lovemaking with her female servant.

The last episode is probably the most substantial of the lot. It is set during the 1400's when the Vatican is ruled by a immoral pope who has sired two children, a cardinal and Lucrezia Borgia (Florence Bellamy). While the pope, the cardinal and Lucrezia indulge in incestuous sexual acts, Savonarola is preaching against the immoralities that are being committed within the church. The episode ends with Savonarola being burned and Lucrezia's baby (one can only guess if it is sired by her pope father or cardinal brother) being baptized into the Catholic religion.

There's not much substance in Borowczyk's collection of episodes. The tales breeze away like forgotten wet dreams filmed in the most fantastically erotic way. The girls seem to give off an incandescent glow that makes the film burst with erotic energy. It is also quite obvious that Borowczyk (like the other prominent European erotica master Tinto Brass) has a little fetish for the female bum as such is very much in prominent display in almost all the episodes (especially the one involving the Countess Bochary). There's so much to be offended at with what's being depicted on screen --- incest, debauchery, sacrilege. However, it is almost a sure thing that Borowczyk meant that the moral angle of the film be taken as an afterthought, instead of as a driving force for the film. It's primary motivation is to tittilate, despite the oddness and the patent immorality of what's on screen. He wouldn't have filmed those sinning girls in loving, tender, and an almost angelic light if his purpose was to preach.