Shake, Rattle and Roll 2k5

Shake, Rattle and Roll 2k5 (Uro dela Cruz, Rico Maria Ilarde & Richard Somes, 2005)

Shake, Rattle and Roll 2k5 is the seventh of the film series featuring three short films that supposedly shake, rattle and roll its audiences (I'm really not sure if those are positive possible reactions to movie viewing). The series started in 1984 with an omnibus featuring three great Filipino directors (Ishmael Bernal, Emmanuel Borlaza, and Peque Gallaga) entrapped in showing their mastery in the horror genre. The rest of the film series primarily belonged to Gallaga and his frequent partner Lore Reyes, with the last two (before this one), being shared by studio directors, including prolific Jose Javier Reyes.

Shake, Rattle and Roll 2k5, instead of being called the seventh of the series, carries the burden of proving that the series has indeed crossed over to the new millennium, infusing the short films with a dose of new tricks learned from the Philippines' Asian neighbors, and some CGI enhancements.

It starts with dela Cruz's portion entitled

Poso (

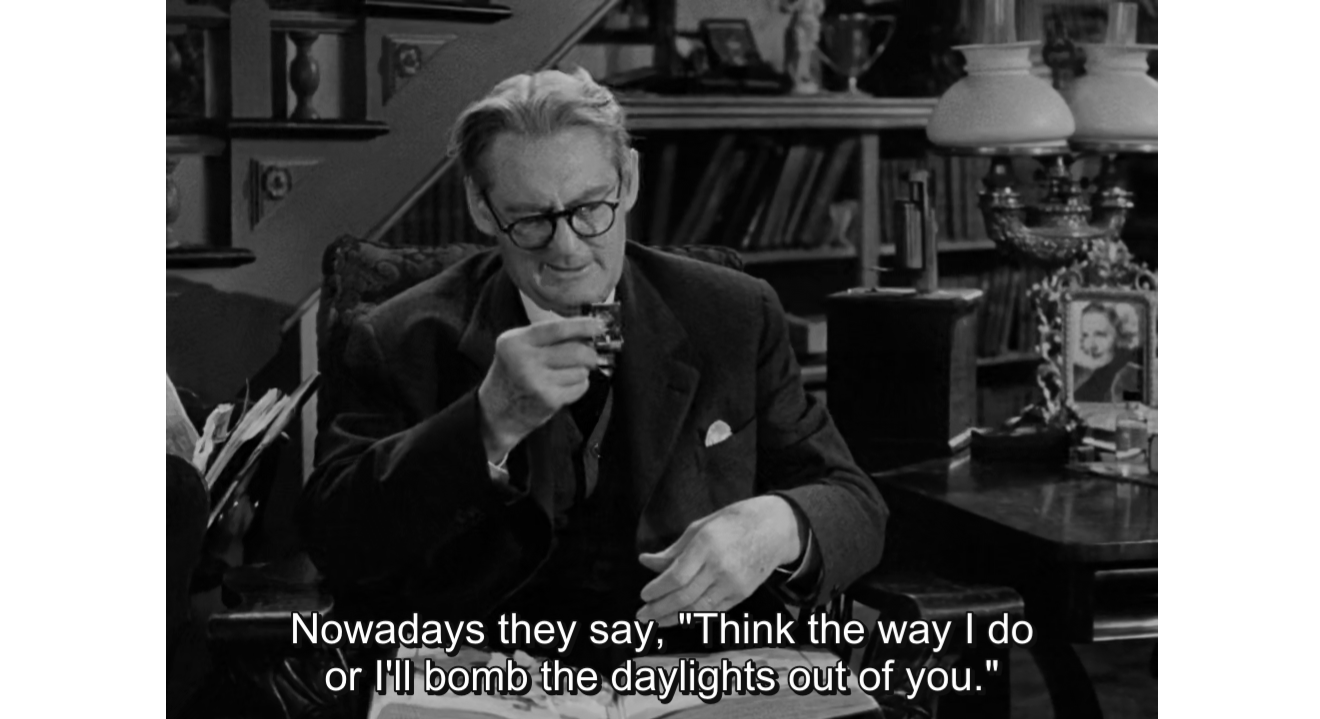

Water Pump). The plot is conventional: about a retiring con artist (Ai Ai delas Alas) who performs her last fake seance with a rich old woman (Gloria Romero) who wants to talk to her dead son. The portion is basically meant for laughs and for children. Delas Alas chews up the screen with her boisterous comedic performance --- which fortunately predominantly works. The attempts at horror are nil (the blob-like CGI creation looks like regurgitated chewing gum --- not really a horrific sight at all), which makes Romero's serious performance and the teenybopper romantic angle out of place.

Rico Maria Ilarde's

Aquarium fares better. It features television comedians Ogie Alcasid and Ara Mina as a married couple who just recently moved into a condominium unit with their son (Paul Salas). They discover a mysterious aquarium which the father fixes up for his son. The mother, wary of her husband's frequent late-night calls and vacation leaves, starts seeing visions of a wraithly old woman warning them against the cursed aquarium.

Ilarde has been in the industry for a while, and has crafted horror films that generally do not follow the conventional trend the rest of Asia is going for. Instead of female ghosts, he opts for rubber-suited monsters and mondo prosthetics. Instead of conventional narratives that go for cheap shocks and plot twists, he opts for bending the genre. He's in his top form when strapped for cash ---

Sa Ilalim ng Cogon (Beneath the Cogon, 2005), a messy yet compelling dive to the wacky (and sometimes corny) unknown, is shot in cheap digital video but is highly regarded in horror film circuits. In

Aquarium, Ilarde tries to mix his cheapie gonzo sensibilities to match the conventions of Filipino studio filmmaking. Ilarde borrows a lot from Hideo Nakata's

Dark Water (2005), but instead of delegating a long-haired ghost as the primary object of horror, opts to go for a rubbery and monstrous envious ghost-kid who, according to the wraithly old woman, was hated by its mother for looking like a goldfish. Ilarde's mixture of his creative sensibilities and the film series' cross-over to the 21st century (Ilarde makes use of digitized sea weeds, which again, is more funny than horrific), and the need to put a domestic issue on infidelity keeps

Aquarium from being truly memorable.

The last portion,

Ang Lihim ng San Joaquin (

The Secret of San Joaquin) throws logic and narrative conventions out the window, and puts the audience in a disquieting unease right from the start. A couple (Mark Anthony Fernandez and Tanya Garcia) escapes from the wife's parents' clutches to start a new life in the faraway town of San Joaquin. Why San Joaquin (a town populated by freaks and weirdos and is just too unsanitary and creepy for a pregnant woman)? Director Richard Somes doesn't really reveal clues to answer any of the questions that might creep into your mind. Instead, he impresses you with a visual energy and a knowhow in film technique and history to mend whatever disastrous plot holes his short film has to offer.

Ang Lihim ng San Joaquin primarily deals with

aswangs. Aswangs are the Filipino version of vampires (but instead of being dashingly debonair in its blood-drinking ways,

aswangs tend to use their elongated tongues and their sharp fangs to devour flesh). It is obvious that Somes has watched a great deal of vampire movies before venturing into filming this. With the help of cinematographer Nap Jamir (who also lensed the lush ghettos of Manila in

Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros (The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros, Auraeus Solito, 2005)), Somes recreates Tod Browning's lighting effect over Bela Lugosi's eyes in

Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931) when the wife lights a candle beside the bust of Christ revealing subtly the identity of one of the townsmen as a creature of the night.

It's not just Tod Browning that Somes borrows from. The

aswangs are fashioned as a Filipinized version of Max Schreck's Orlok in F. W. Murnau's

Nosferatu (1922). The lighting and the editing acknowledge German Expressionism as put into work in a Southeast Asian landscape ala Canadian Guy Maddin's modernization of the silent film. The

aswangs surrounding the house of the couple is a throwback to George Romero's

Night of the Living Dead (1968). Mark Anthony Fernandez's unflinching machismo is an acknowledgment to all the irrational heroes of

Predator (John McTiernan, 1987), and other cult horror flicks.

It's a dizzying ride that dazzled my senses within the span of the short film, that welcomes Somes (who worked for Erik Matti as production assistant) as a bright new director who understands and comprehends film history relating to film production. If you have to sit through Uro dela Cruz's trite

Poso and Rico Maria Ilarde's interesting yet surprisingly conventional

Aquarium to see Somes'

Ang Lihim ng San Joaquin, then I suggest you do because it is really worth it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

wm.jpg)