.jpg)

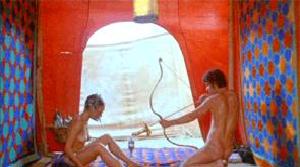

A Review of Roberto Rossellini’s The Flowers of St. Francis

By Francis Joseph Cruz

Francis, rising from prayer, is obviously distraught. His usually calm face is shaking in distress and moist with fresh tears. His prayer, where he lays face down on the ground murmuring “Jesus, nailed on the cross” in between sobs, is more o an act of contrition than a dialogue with God. A leper, his beggarly clothes barely covering the open sores that populate his flesh, walks by. Francis, upon seeing the beggar nearing his spot, covers his face in sadness. He follows the leper and stops to acknowledge him. The leper walks away. He again follows the leper and stops to acknowledge him. The leper walks away. Still undaunted by the repetitive inattention given to him by the leper, he follows him, stops, and embraces the outcast. The leper still walks away, but stops before he gets too far, and looks back at Francis. Francis remains and lays anew among the flowers under the night lighted by his Sister Moon.

The scene described above is merely one of the episodes plucked from The Little Flowers of St. Francis and The Life of Brother Ginepro, two important Franciscan texts that detail the life of the saint and one of his followers, and immortalized into screen by neorealist director Roberto Rossellini in his 1950 masterpiece, Francesco, giullare di Gio (literally translated as Francis, the Jester of God but more popularly known as The Flowers of St. Francis). Filtered from the scene or most of the scenes of the film is the comfort of resolution.

The episodes are mostly portraits of the monks’ daily life, characterized by their childlike naïveté and upright selflessness. In fact, all innocence, humility and goodwill, as exemplified by the leper’s unemotional reaction towards Francis’ act of piety, are often rewarded with indifference, annoyance and violence. The film, narratively unstructured and connected theoretically by an indefinable atmosphere of spiritual serenity, is historically placed between the period of Pope Innocent’s acknowledgement of Francis’ spiritual movement and the period where Francis orders his followers to preach in different parts of the world. With that historical perspective, the film persists as a document of faith, against an overpowering lack of any proof to the existence of a God as professed by the abundance of unkindness despite the dogmatic intervention of the Church.

The film was made during the time Rossellini was publicly decried for having an affair with Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman. The two were married to different people, but have met during the filming of Stromboli. Despite the emotional turbulence brought about by the scandal, The Flowers of St. Francis remains almost unnaturally serene. Not only that, Rossellini is a self-professed atheist. However, the film, with its clear and convincing exaltation of faith, is probably one of the most poignant and effective films about a religious figure of all time.

In comparison to the guilt-ridden and arguably hateful excesses of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ and the humanizing intimacy of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, Rossellini’s film seems inconsequential with its insistence on the mundane, the banal, and the quizzical spiritual implications of such simplicity. Yet, its lack of indulgence, its humility, and concern to the action rather than the effect, postulates the very essence of faith: that it is personal and does not require evidence. Had Rossellini decided to exalt Francis and his monks with the immensity of their work, then its definition of faith would have been compromised, making it less a film and more of a didactic Catholic propaganda.

The film ends with Francis and his monks, after giving away all of their possessions to the poor, decide to part to preach their ways. A monk asks where they should go. Francis tells them to spin until they are dizzy; the direction in which they land will be the direction they should go to and preach. They separate as Rossellini’s camera reveals the sky, calm yet uncertain. Faith is exactly that, calm yet uncertain. The Flowers of St. Francis gains more pertinence in these uncertain times, where faith, despite the ease of claiming possession of it, is an unfamiliar, if not completely rare, fragrance.

(First published in The A/V Club, Philippine Star, 26 March 2010)

wm_p1.jpg)